Ethereum to MultiversX migration guide

Introduction

In the last period smart contracts suffered a rapid growth as many blockchains brought on the table better and better ways to develop one. In this article we will make a short comparison between writing a smart contract in Ethereum and one in MultiversX, and bring you another perspective from the Ethereum background to what could be an amazing experience of developing in Rust with SpaceCraftSDK - MultiversX’s framework.

SC in Ethereum vs MultiversX

The Ethereum execution client relies on Solidity as its programming language, even though it provides several implementations and support for multiple other languages such as Javascript, Rust, Python, Java, C++, C# and Go.

On the other hand, the MultiversX virtual machine (VM) executes WebAssembly. This means that it can execute smart contracts written in any programming language that can be compiled to WASM bytecode. However, MultiversX strongly encourages developers to adopt Rust for the smart contracts by providing a strong Rust framework which allows for unusually clean and efficient code in smart contracts, a rarity in the blockchain field. A declarative testing framework is bundled as well.

The MultiversX VM was built to be a fast and secure execution engine, stateless and to allow asynchronous calls between contracts in the most transparent way possible to the user.

Let’s take a look to a simple adder contract in Ethereum’s Solidity

contract Adder {

uint private sum;

constructor(uint memory initialValue) public {

sum = initialValue;

}

function add(uint value) public {

sum += value;

}

function getSum() public constant returns (uint) {

return sum;

}

}

This would translate in MultiversX’s Rust into:

#[multiversx_sc::contract]

pub trait Adder {

#[init]

fn init(&self, initial_value: BigUint) {

self.sum().set(initial_value);

}

#[endpoint]

fn add(&self, value: BigUint) {

self.sum().update(|sum| *sum += value);

}

#[view(getSum)]

#[storage_mapper("sum")]

fn sum(&self) -> SingleValueMapper<BigUint>;

}

The element that defines SpaceCraftSDK is the fact that by a series of implementations the whole structure of smart contracts is drastically simplified. SpaceCraftSDK offers a series of annotations that transforms basic rust elements such as functions, traits into smart contract specific elements such as endpoints, storage mappers, modules etc.. In this way, for example, a method marked with #[endpoint] makes it public to be called as an endpoint of the contract.

Handling the storage

Contracts in MultiversX are important to be as small as possible, the reason why the whole storage is not handled by the contract, but rather the VM, the contract only holding a handle of a memory location inside the VM where the data is actually stored. A very popular concept that you will see here is the one of storage mappers, which are some structures designed to handle the serialization inside the storage, depending on the data types.

In the contract example the annotation above the declaration of sum is a storage mapper holding a single value of type BigUint. This mapper allows accessing and changing the value of our variable stored in the assigned memory location inside the VM. For multiple particular uses we implemented a series of mappers of which you can find out more about in our documentation.

Despite the fact that Ethereum also advances towards a similar concept of storage, the possibilities on MultiversX are more vast due to an optimisation made at the level of memory allocation which leads to saving up gas and ultimately speeding up execution.

The dynamic allocation problem

One of the main issues of some Rust types such as String or Vec<T> when it comes to smart contract development is that they are dynamically allocated on heap, meaning that the smart contract asks for more memory than it actually needs from the runtime environment (the VM). For a small collection this is insignificant, but for a bigger collection, this can become slow and the VM might even stop the contract and mark the execution as failed. Not to mention that more memory used leads to longer execution times, which ultimately leads to also increased gas costs.

One of the most important outcomes of this issue is the fact that MultiversX smart contracts don’t use the std library. You will always see them marked with #[no_std].

The solution to this problem, that the developers of MultiversX came with, is called managed types. These managed types are the key elements behind the concept with the VM handling the smart contract memory that we mentioned before. Inside the contract these managed types only store a handle, which is a u32 index representing the location within the VM memory where the data is stored.

With that being said, here’s a list of managed counterpart data types to use in MultiversX smart contracts:

| Unmanaged (safe to use) | Unmanaged (allocates on the heap) | Managed |

|---|---|---|

| - | - | BigUint |

&[u8] | - | &ManagedBuffer |

| - | BoxedBytes | ManagedBuffer |

ArrayVec<u8, CAP>[^1] | Vec<u8> | ManagedBuffer |

| - | String | ManagedBuffer |

| - | - | TokenIdentifier |

| - | MultiValueVec | MultiValueEncoded / MultiValueManagedVec |

ArrayVec<T, CAP>[^1] | Vec<T> | ManagedVec<T> |

[T; N][^2] | Box<[T; N]> | ManagedByteArray<N> |

| - | Address | ManagedAddress |

| - | H256 | ManagedByteArray<32> |

| - | - | EsdtTokenData |

| - | - | EsdtTokenPayment |

Data serialization

All data that interacts with a smart contract is represented as byte arrays that need to be interpreted according to a consistent specification defined in MultiversX’s framework, named SpaceCraftSDK. This format is aimed to be somewhat readable and to interact with the rest of the blockchain ecosystem as easily as possible, the reason why all numeric types follow the big endian representation.

We mentioned before that dynamic sized variables have their size calculated at compile time, the reason why we know the size of the byte arrays entering the contract. All arguments have a known size in bytes, and we normally learn the length of storage values before loading the value itself into the contract. This gives us some additional data straight away that allows us to encode less. We can say here that our data is represented in its top-level form, reading from the storage is done by zero size deserializing.

We implemented a concept called ManagedType which is a trait that many of our data types possess, allowing a more efficient way to hold them internally.

Lets take for example an endpoint having an optional parameter. Option as you know has 2 possible elements: an empty value representing none or a parameter encrusted in something representing some. Putting a small restriction for this parameter to be one of a kind in an endpoint we can assume that if by the time we reached it, if there are no bytes left to cover, we have a none, or if we have straight up a parameter of the type we specified, than we have the some option. Imagine now that we also extended this principle to a multivalue type attribute having the same logic behind.

Because of these optimisations MultiversX’s provides one of the most efficient and cheap ways to interact with a smart contract on the blockchain.

Fees in MultiversX

An usual term met on blockchains when it comes about fees is gas, which translates to the unit measuring the computational effort to execute specific operations on the blockchain.

Usually these gas costs for each blockchain are paid in the blockchain’s native currency.

For Ethereum for instance, there is something called gwei, an unit equal to one-billionth of an ETH, or 10-9ETH. These fees have a tendency to grow depending on how crowded the network is. You can think of the gas cost as a result of a formula something like: units of gas used * (base fee + priority fee), where the base fee differs per block, and will increase by a maximum of 12.5% per block if the target block size is exceeded.

The priority fee (tip) incentivizes validators to include a transaction in the block. Without tips, validators would find it economically viable to mine empty blocks, as they would receive the same block reward.

For MultiversX, the gas used within the contract is terminologically separated from the unconsumed remaining gas. Here the processing time breaks the consumed gas into two components:

- gas used by

value movement and data handling - gas used by

contract execution(for executing System or User-Defined Smart Contract)

The value movement and data handling component is defined by the formula:

tx.gasLimit =

networkConfig.erd_min_gas_limit + networkConfig.erd_gas_per_data_byte * lengthOf(tx.data)

whereas the contract execution despite being easily computable for System Smart Contracts, it is harder to determine a priori for user-defined Smart Contracts. This is where simulations and estimations are employed.

Finally, the processing fee used by the MultiversX blockchain looks something like this:

processing_fee =

value_movement_and_data_handling_cost * value_movement_and_data_handling_price_per_unit +

contract_execution_cost * contract_execution_price_per_unit

Let's look at some actual numbers!

Based on https://etherscan.io/txs and https://beaconcha.in/charts/validators Ethereum at the moment of writing this tutorial had 1,135,937 transactions in the last 24h with an average transaction fee of 2.47 USD with 1,031,453 active validators.

On the other side, MultiversX from their source (https://explorer.multiversx.com/) had 217,263 transactions in the last 24h with an average fee of 0.02 USD with 3,323 validators, which makes 100 times cheaper than a transaction on Ethereum.

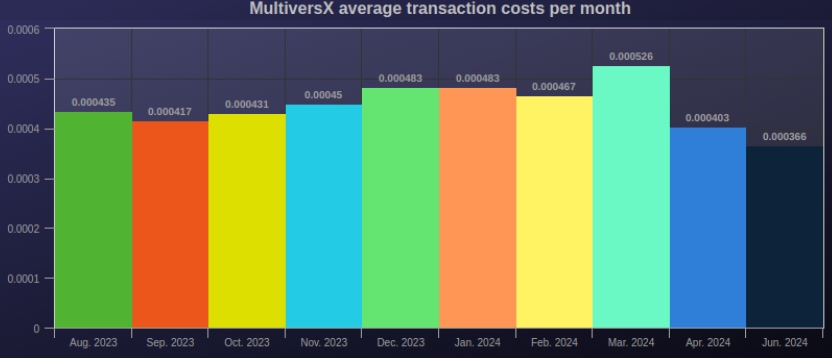

As you can see in the histogram above, the costs of the transactions on the MultiversX blockchain kept low. Note that the prices you see are in MultiversX’s native coin EGLD.

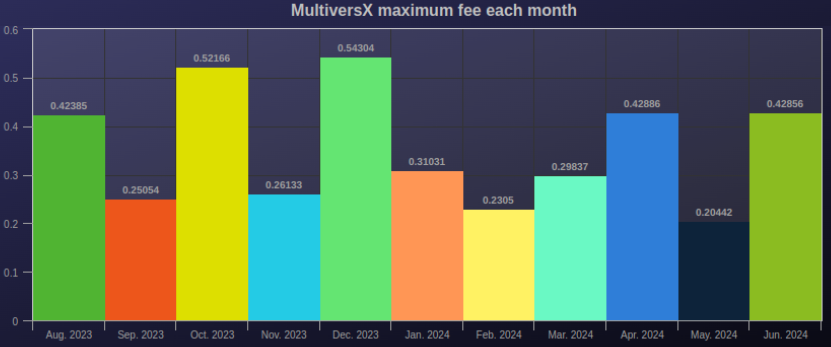

While sometimes when the Ethereum Network gets crowded the fee of a single transaction could easily jump over 47. Similar to the first histogram, the prices you see in the one with maximum transaction fee each month are in MultiversX’s native coin EGLD.

Token standards

When it comes to tokens, Ethereum comes with a couple standards that ensure the smart contracts composability. Most of them are well known:

ERC-20- a standard for fungible & interchangeable tokens such as voting tokens, staking tokens or virtual currenciesERC-721- a standard for non-fungible tokens such as deeds for artwork or songsERC1155- a standard for fungible tokens, non-fungible tokens or other configurations such as semi-fungible tokens used for more efficient trades and bundling of transactions

On the other hand MultiversX comes with a standard called ESDT (eStandard Digital Token) used to manage fungible, non-fungible and semi-fungible tokens at protocol level. The important aspect about MultiversX tokens is that they don’t require a dedicated smart contract for issuing. The direct implication of this element is that custom tokens are as fast and as scalable as the native EGLD token itself. Furthermore, the protocol employs the same handling mechanism for ESDT transactions across shards as the mechanism used for the EGLD token.

Technically, the balances of ESDT tokens held by an account are stored directly under the data trie of that account. It also implies that an account can hold balances of any number of custom tokens, in addition to the native EGLD balance. The protocol guarantees that no account can modify the storage of ESDT tokens, neither its own nor of other accounts.

Transactions in MultiversX

We decided to model all transactions using a single object, but with exactly 7 generic arguments, one for each of the transaction fields.

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Environment | Some representation of the environment where the transaction runs. |

| From | The transaction sender. Implicit for SC calls (the contract is the sender), but mandatory anywhere else. |

| To | The receiver. Needs to be specified for any transaction except for deploys. |

| Payment | Optional, can be EGLD, single or multi-ESDT. We also have some payment types that get decided at runtime. |

| Gas | Some transactions need explicit gas, others don't. |

| Data | Proxies (ideally) or raw |

| Result Handlers | Anything that deals with results, from callbacks to decoding logic. |

Each one of these 7 fields has a trait that governs what types are allowed to occupy the respective position.

All of these positions (except the environment Env) can be empty, uninitialized. This is signaled at compile time by the unit type, (). In fact, a transaction always starts out with all fields empty, except for the environment.

For instance, if we are in a contract and write self.tx(), the universal start of a transaction, the resulting type will be Tx<TxScEnv<Self::Api>, (), (), (), (), (), ()>, where TxScEnv<Self::Api> is simply the smart contract call environment. Of course, the transaction at this stage is unusable, it is up to the developer to add the required fields and send it.

In its most basic form, a transaction might be constructed as follows:

self.tx()

.from(from)

.to(to)

.payment(payment)

.gas(gas)

.raw_call("function")

.with_result(result_handler)

Ultimately, the purpose of a transaction is to be executed. Simply constructing a transaction has no effect in itself. So we must finalize each transaction construct with a call that sends it to the blockchain.

In SpaceCraftSDK the transaction syntax is consistent, the only element differing being the execution. More specifically:

In a contract, the options are .transfer(), .transfer_execute(), .async_call_and_exit(), .sync_call(), etc.

In unit tests written in Rust just .run() is universal.

In interactors, we call .run().await. It's the same method name, but this time it's asynchronous Rust, so it can only be called in an async function, and .await is necessary.

Let's dive into an example!

In Ethereum a transfer requires a couple of implementations of some functions of a ERC721 standard.

import "./erc721.sol";

function _transfer(address _from, address _to, uint256 _tokenId) private {

balance[_to]++;

balance[_from]--;

tokenOwner[_tokenId] = _to;

emit Transfer(_from, _to, _tokenId);

}

function transferFrom(address _from, address _to, uint256 _tokenId) external payable {

_transfer(_from, _to, _tokenId);

}

In MultiversX making a token transfer is done simply without any other requirements as follows:

#[payable("*")]

#[endpoint]

fn transfer(&self, to_address: ManagedAddress) {

let payment= self.call_value().single_esdt();

self.tx()

.to(to_address)

.single_esdt(&payment.token_identifier, payment.token_nonce, &payment.amount)

.transfer();

}

An essential element of the MultiversX smart contract is that every smart contract is also an account, just like a normal user, meaning that it also has an address and a balance and it can perform transactions. From this perspective we can say that transfers in MultiversX are always done from the address of the contract, and in that case, before the transaction the tokens have to be owned by the contract.

Smart contract differences

Upgradable contracts

Just as in Ethereum a contract has an initiator, in MultiversX as an init function, and if needed also an upgrade, allowing the builder to define behavior when the contract gets upgraded. The upgrade function is similar to the init function, but named accordingly and preceded by the #[upgrade] annotation.

Mapping

As storage mappers were previously mentioned, let's talk about mapping.

In a Ethereum contract as many times you would like to simply map an address on its balance, element simply done by mapping(address => uint) public balances.

For a MultiversX contract would translate to a storage mapper such as:

#[storage_mapper("balance")]

fn balance(&self, address:ManagedAddress) -> SingleValueMapper<BigUint>;

In this syntax we mapped to an address a storage of a single value type containing a BigUint representing the balance. The greatest part of this is that if at one point we want this balance to be accessible public for viewing the storage mapper can just be preceded by an annotation such as #[view(getBalance)] allowing anyone that queries this mapper to see the balance of a given address.

Furthermore the balance can be easily set in any endpoint by calling self.balance(my_address).set(my_value);

Building an EVM project on MultiversX

Lets take a simple voting contract in Solidity:

pragma solidity ^0.6.4;

contract Voting {

mapping (bytes32 => uint256) public votesReceived;

bytes32[] public candidateList;

constructor(bytes32[] memory candidateNames) public {

candidateList = candidateNames;

}

function voteForCandidate(bytes32 candidate) public {

require(validCandidate(candidate));

votesReceived[candidate] += 1;

}

function totalVotesFor(bytes32 candidate) view public returns (uint256) {

require(validCandidate(candidate));

return votesReceived[candidate];

}

function validCandidate(bytes32 candidate) view public returns (bool) {

for(uint i = 0; i < candidateList.length; i++) {

if (candidateList[i] == candidate) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

}

With this model in mind, the MultiversX implementation would look like:

#![no_std]

#[allow(unused_imports)]

use multiversx_sc::imports::*;

#[multiversx_sc::contract]

pub trait Voting {

#[init]

fn init(&self, candidates: ManagedVec<ManagedBuffer>) {

for candidate in &candidates {

self.candidates().insert(candidate);

}

}

#[endpoint]

fn vote_for_candidate(&self, candidate: ManagedBuffer) {

require!(

self.candidates().contains(&candidate),

"Name not in candidate list"

);

self.votes_received(&candidate).update(|votes| *votes += 1);

}

#[view(getCandidates)]

#[storage_mapper("candidates")]

fn candidates(&self) -> UnorderedSetMapper<ManagedBuffer>;

#[view(getvotesReceived)]

#[storage_mapper("votesReceived")]

fn votes_received(&self, candidate: &ManagedBuffer) -> SingleValueMapper<u32>;

}

Notice that the candidates from the Solidity contract in MultiversX’s contract translate into a storage mapper of type UnorderedSetMapper. This mapper was specially designed to allow easy and cheap access to a list of elements stored within at the cost of its ordering. Checking whether a candidate exists within the list or not becomes simple by just calling self.candidates().contains(&candidate).

Next we have the increase of the number of votes which is done by self.votes_received(&candidate).update(|votes| *votes += 1);. Here update receives a lambda allowing a total control of the contents of the storage.

The implementation of totalVotesFor becomes redundant in MultiversX thanks to the #[view(getvotesReceived)] annotation which gives our votes_received storage view access on blockchain.

Interactors

While Ethereum implemented its own tool to facilitate deployment and interaction with smart contracts, the developers at MultiversX went on an approach facilitating these elements from the same IDE, within the same framework, and by writing mostly the same Rust syntax as in the smart contract itself.

For MultiversX, the Interactors have multiple purposes, besides just helping you deploy a smart contract on the blockchain. These interactors work side by side with another tool developed by MultiversX developers called sc-meta which facilitates smart contract building and proxies and interactor code auto-generation.

By using sc-meta one can easily be straight up ready to interact with his smart contract by generating his interactor with sc-meta all snippets.

Let’s take the Adder contract presented at the beginning of this tutorial. By generating its interactor we would obtain something like this:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

env_logger::init();

let mut args = std::env::args();

let _ = args.next();

let cmd = args.next().expect("at least one argument required");

let mut interact = ContractInteract::new().await;

match cmd.as_str() {

"deploy" => interact.deploy().await,

"getSum" => interact.sum().await,

"add" => interact.add().await,

_ => panic!("unknown command: {}", &cmd),

}

}

This interactor code now allows us to simply interact with the contract straight up from the command line.

Making a deploy is easily done by simply calling interactor % cargo run deploy. By running this deploy command a new state.toml file will be generated containing the newly deployed address.

As you might see in the interactor code, all the expoints of the smart contract are easy to call in the same manner as the deploy.

BackTransfer

One great Feature, the developers of MultiversX came with was due an element regarding its old VM. Back then if a parent SC called a child SC and the child SC transferred back tokens to the parent, it must have called a “deposit” function and the parent SC had to register that deposit into a storage. After the child SC execution was finished, the execution of parent SC was resumed and where we had to read from the storage, what kind of transfers the child did towards itself.

Another problem with this, is if the parent SC was not payable by SC and the child SC did not call deposit, only transfers, the execution would have failed. This was even more complicated in asynchronous calls. It was discovered that if a child SC is not well written, a malicious parent SC can become problematic for the child SC. One example was the liquid staking contracts, where unbonded funds could get lost because a malicious parent SC was not payable by SC.

So MultiversX decided to change its paradigm: When a parent SC calls a child SC and the child SC does a set of transfers to the parent, the payable check is skipped for the parent. The check is skipped even if the parent SC called the childSC with asyncCall and even if the child SC is in another shard compared to the parent SC.

Technically speaking: All transfers without execution from the child SC to the parent SC are accumulated in a new structure called backTransfers. In the end the parent SC can do the following <payments, results> = ExecuteOnDest(child). This makes DeFi lego blocks easier to create.

The accumulated backTransfers can be read by the parent SC by calling the managedGetBackTransfers VM API.